inspiration + perspiration = invention :: T. Edison ::

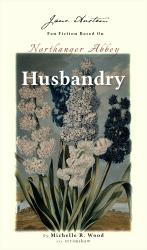

A mashup of Jane Austen, Virgil, and Aristophanes, with Henry Tilney in the dual roles of Orpheus and Dionysus. Bordering on crackfic, beyond meta. Now available as an eBook via Draft2Digital (bundled with Trifles Light as Air).

It was a sad day when Catherine Tilney née Morland was buried at the same church where she had so lately been married. Neither cleric present felt up to the task of officiating, and it was largely up to Mr. Morland's curate to ensure the service was performed. Henry composed a very eloquent eulogy which he delivered at the graveside, and all agreed he never looked so ministerial as at that moment. Yet though words had often been his closest companions and comfort, they offered no balm for Henry's present suffering. Rather they felt stupid and empty, a vain attempt to embody the lady whose life had been so cruelly cut short by a terrible, capricious fate.

The Morlands invited him to stay as long as he wished, and his sister just as generously offered to take him anywhere he might like to travel. Yet Henry was unable to fathom doing more than beg a week to consider what he would do. He walked along the paths Catherine had loved and went everywhere he could remember her describing; and though Henry talked as often as possible with those who had known his wife so well, nothing served to fill the awful emptiness of his heart. Everyone in the parish agreed Mr. Tilney was to be pitied above all else, but also that mourning very much became him: he spoke so well, and with such fervor, it inspired answering admiration with any who heard him.

"And really," Mrs. Allen said to Mrs. Skinner, "if he were not always speaking of her, I could see Mr. Tilney exciting any number of ladies' hearts; he always has been a very agreeable, fine young man. I must see about introducing Sally to my dressmaker."

But Henry was not thinking of ladies, or dancing, or any of his usual hobbies. Even when speaking to Eleanor, his dearest friend, he could not help feeling restless and uneasy. He saw her pitying looks, and knew she meant his good when drawing him into conversation on any other subject, but he could not adequately explain what so depressed his spirits. It was not simply Catherine's death; mourning was not unknown to him. Nor was it the added disappointment of not having consummated the marriage of his heart, though he grieved this loss as well.

No, what plagued him was the utter imbecility of the entire episode, causing him to abandon company for the respite of more solitary walks and time to think through matters. How, he wondered, could so undeveloped an antagonist intrude so preposterously late into the plot? What logic could there be in the sudden personification of Lucifer, never foreshadowed during their courtship and so unlikely to be found in this mundane setting? Wherefore these absurd disturbances in weather and whereabouts, equipages and equines? He could believe God and Heaven might allow the just and the unjust alike to die, as Scripture clearly taught; he did not credit Providence so fantastically vengeful as to take his bride by means outside of those set by the laws of reason, probability, and nature.

At last his puzzling led him to one conclusion: Catherine's death had been a peculiar, cosmic mistake. He realized how mad it sounded; he was certain telling anyone of his thoughs would cause nothing but pain and distress to those already sharing concerned whispers when they thought he was out of hearing. But just as he had not let his father bully him into accepting the loss of his beloved prior to marriage, Henry was determined not to let anything so stupid as an error, even of supernatural origin, keep him from her now. With this thought in mind he sat down to pen a letter, laboring over it with all the practice contained from their recent season of clandestine correspondence, and sent it to London with all his prayers and hopes.

In less time than was to be expected, he received his answer, and read it with eager anxiety:

"Dear Reverend Tilney,

"I was much astonished to receive your note, and have debated whether it would be kinder to reply or not. But though I have lately been uninspired to meet the public's demand for literature, yet I could not resist the opportunity to give whatever solace my words may contain. Your situation must provoke sympathy from any who read of it; and I am not immune to the flattery of understanding that one of your late wife's chief attractions was the appreciation you both shared for the work of novelists, including that of your humble correspondent. There is no greater compliment than to credit the pleasure of one's love as inspired, even in part, by the pen of another. Therefore I have determined to act as you desired, and have included the pages you requested I write, with no demand for payment except the gratifying notion that this simple fiction may be of some service in guiding you to a place of restoration and cheer. I have left the ending open according to your wishes; may you complete it yourself with all the grace to be found this side of our final rest. In the worst of times it is useful to recall that though human nature is stained by the calumny of sinful disruption, yet even before that happy day when the revealtor's prophesies will be made complete we may find humor and joy through the powers of our mind and the best-chosen language.

"Believe me," &c.

"Mrs. Radcliffe"

The pages that fell into his lap after this encouraging epistle were taken up at once. After a thorough examination of all they contained, he performed three activities in rapid succession: he offered thanksgiving to his Lord, further gratitude in written form to the authoress of said deliverance, and then went in search of his sister with a request.

"You wish to go to Milford, alone?" Eleanor was all concern.

"I know it is asking much." Henry found it no trial to keep calm now that he had a purpose in mind; in fact, it was increasingly difficult to appear properly oppressed, and he attempted a more melancholic air. "But there is a personal matter I would undertake, one having to do with Catherine, and I would like to complete it without company, even your own dear self. Know I would not ask if I had not very good reason, and I promise when I return to explain myself more candidly."

"If you feel you need to, of course we will help," was her reply, "but take care Henry: I could not bear to lose you as well."

He felt some pangs when assuring her he would do everything in his power to prevent that fate; had his sister been aware of his errand, he was sure she would accuse him of playing her false. But he meant his promises with every fiber of his being. For Henry was determined not only to deliver his own person back to her, but she who was loved by them both.

The Viscount's carriage was readied and Henry lost no time in hastening to the coast, using the time to read and reread Mrs. Radcliffe's writing. It began with the warning that while she usually contented herself with the machinations of foreign shores, this tale would involve a very English port, even older than the race inhabiting it now. "For such as our ancestors, brave souls ahead of even the Roman invasion, used this place for their defense, as another more famous poet (also more prone to the ways of Danes and Italians) has described in his own history of that afflicted king of the Britons known as Cymbeline. It is to that blessed bastion of our ancient past I begin, the constant beacon of our hopes and fears."

The town that greeted Henry's arrival did not appear as a gloomy portal to antiquity; the newly built harbor and shops, and fresh boats along its wharf, belied any connection to history or myth. Our hero did not allow these modern activities to baffle him but dressed in his darkest blacks; and with a fresh hyacinth secure in his hat, he followed his directions out into the countryside toward the relics of a medieval chapel. Henry enterted the the crumbling ruin with caution and found the altar, while disused and covered in debris, still intact. Upon examination of this edifice he could no longer claim surprise in discovering the same signs promised by his pages: for into the stone was the outline of a door, and Henry had only to push to find a passage contained behind it.

It was not as dark inside as he had expected, nor did he seem to be descending deep below the ground. Indeed, he thought he heard the wind and the rush of water nearby. It soon became apparent he was ascending on steps carved into the rock, and it was not long before he came to a wooden gate which opened to a pier where a small boat was tethered. Approaching it, Henry saw the man on board wore no uniform but instead the rustic garb of a primordial yeoman out of some story never written by lettered minds. The sailor looked up and greeted him by name.

Henry started despite himself at this further departure from the ordered world, but smiled all the same. "I thank you for your courtesy. May I ask, where do you sail to?"

"That depends," the ancient mariner replied, "and as I know you have not died by hanging, poison, or accident, I do not see how I may accommodate you. My task is not to ferry the living to their destinations."

"But surely you might allow a visit, if I were to help with the boat?"

"And are you a sailor? A laborer? A soldier? What profession gives you currency for this journey?"

Henry considered the plight of his own inabilities. "I am but a young parson: I have a decent education, a good living, and only the modest virtues of my wits and humor to distinguish me from my fellow man. But I have on occasion had cause to lift their hearts with my words, and am fond of stories: I would be glad to provide you with any entertainment desired."

His offer was considered, and at last the man nodded. "I will take you where you wish to go, but you must keep your word and not be distracted from your purpose. As a mortal you are susceptible to all the vagaries and temptations this passage contains; if you become enamored with any other beyond the intention of your heart, you will be lost beyond what help I may provide."

"Agreed, and my thanks for your warning. Now, what fable would you have me recount?"

"You might begin with Troilus and Criseyde, as a remembrance of what fate you are bent on unmaking."

Stepping into the boat and taking a seat, Henry smiled more broadly. "I hope you will accept Shakespeare's account over Chaucer's; regardless, I do not fear to speak of one woman's inconstancy, knowing the vice is so evenly dispersed among the sexes, and that she whom I seek is the epitome of the opposite virtue."

They set off, and Henry found that he fell into the same rhythm of the boatman's oars as he went up and down the conceits of the play, first raising the poor lovers into the height of passion before sinking them into mires of fear and distrust. It was as he struggled to recall some speeches in the fourth act, skipping or reworking any lines he could not catch in his mind, that he became aware of murmurs nearby. They were alone upon the water yet in looking about he found the waves held traces of forms, some eerily familiar. As he assumed the role of the sad Trojan prince, who despaired of ever seeing his true love again, Henry could not help turning his head when he heard a line from a different play altogether, and recognized Romeo calling to Juliet at her balcony.

Remembering the admonition to avoid the influence of this strange sea, Henry attempted to keep up his own words even as more sirens assailed him: Virgil's Aeneas, the Bard's Portia, Marlowe's Faust. But it was not noble creations alone who caused him to look first this way and that, his story dropping in spurts as he was beguiled by the absurdities of Ensign Beverley with his languishing lady, Molière's miserly villains, and the many lovers of Camilla. It was as if every cherished character were alongside him, all speaking at once, and yet all clearly understood: he need only turn his ear a little to enjoy first one, then another.

He lost his train of thought completely. Which speech had he last spoken? Or what scene delivered? Which tale had he begun? What did it matter when poor Emily and hapless Gulliver beckoned? He barely realized how far he had leant over the boat's side, the better to hear and enjoy the rippling dialogue, nor how close he was to going over completely. It seemed he need only step forward and he might be the Harlequin, or Hero, or any part he pleased.

It was only his hat that saved him, for as Henry bowed low it hit the waves first; and he was made aware of his danger when he recognized it sailing away upon the tide, the purplish flower it held catching his attention in time. Flinging himself back into the boat, he shut his eyes and stopped his ears, willing all other specters to fade save Catherine's sweet face. When at last he felt his senses returned, Henry haltingly started back upon the final act of the play. With deliberate absorption in the progression of these words rather than the sounds around him, Henry never stopped his speech even when he finished the play and had to depend on his own imaginings. He might have spent a lifetime thus, dead to anything else, had the sailor not roused him.

"We have arrived: you are safe to disembark. But mind your way. Remember you are yet mortal and may still be caught unawares."

Henry thanked him most heartily, and before parting asked if there was anything else he might do for the man. "I fear I was a very poor companion."

The boatmen had already taken up his oars, and shook his head. "You were better than most, and braver than many. If you would do me kindness, care as much for the living as you do for those who never breathed." With this parting advice he rowed back onto the fantastic sea.