inspiration + perspiration = invention :: T. Edison ::

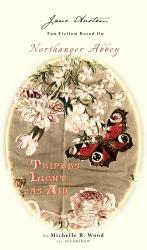

A collection of one-shots based on Northanger Abbey: drabbles, flash fiction, missing scenes, and more. Title from Shakespeare's Othello, as quoted by Jane Austen in Chapter One. Now available as an eBook via Draft2Digital.

Henry had dreaded the day when the good Dr. Prewitt might involve himself in the Tilney quarrel; or, what was more likely, be drawn into it by his patron. Genuine respect and affection for the man, not only as a neighboring vicar but also his many years of service both to Northanger's church and its chief family, made Henry loathe to cast his burdens on that worthy soul. The quiet passage of weeks and months dulled this fear to a barely remembered unease.

An invitation to tea brought all these apprehensions back. Still, Henry felt obligated to accept any potential means of mending the current breach no matter how slight. It was not impossible for his father to act via proxy.

Dr. Prewitt was delighted to receive him, and while mouthing the same platitudes of twenty years earlier, was at least sincere in his addresses. The previous day's service naturally formed the first topic of conversation, which led to discussion of their respective parishes and then to theology in general. The tea was very good; in fact, so good, Henry could not help commenting on it.

"Yes, thank you, my nephew has recently been to the East Indies and sent the gift, I find it very refreshing." Nothing more was said about this particular relation out of both person's long habit avoiding any discussion of the navy. Instead, Dr. Prewitt changed the subject to ask after Captain Tilney.

"You would likely know better than myself," Henry answered. "I enjoyed but a single letter this past summer."

"Dear me, I hoped you had received something more substantial; I do not believe your father has heard anything since his regiment left the country."

"No great surprise, given my brother's current occupation and the accounts we read in the newspapers."

"We must pray for his safe return."

"Amen."

"For—" Dr. Prewitt continued, ignoring the finality of the last comment— "though it is unpleasant to think of, and we must always trust to Providence, one can never be too confident. Just look at the case of your sister's new husband. Who would have thought he should inherit? and yet he is now in possession of many blessings."

"I hope domestic felicity counts chief among them."

"Agreed. But it does force contemplation of the future's uncertainty; your father must be greatly concerned about his sons."

There was no ignoring the plural on the last word, nor the expressive look accompanying it. Henry sipped at the bitter dregs left in his cup before speaking. "I would not venture to guess at my father's state of mind. My prayers, as ever, are for my brother's safe return and the perseverance of the nation, which I trust are shared hopes among all are friends."

"One would think so, and yet we have so many examples now of those who should be stalwart defenders of the throne and the church printing the most seditious articles; even, I hear, preaching the most serious heterodoxy. It is a fearful thing when those who claim to be of our own sect turn against the wisdom of the ages."

"Yet we must pray that all will work according to the Lord's good purposes. It puts me in mind of Abraham, and the faith he exhibited in raising Issac only to receive him back again. There may be some parallels that could be applied at the upcoming celebration of our king's reign."

"Perhaps. Although, rather than the ram substituted for the promised son, we might consider the lost lamb returned to the flock. Or, indeed, the prodigal welcomed home by a grateful parent. There can be no better demonstration of our Lord's patience in welcoming home he who has wandered astray."

"True: the parable's father is all benevolence and generosity, forgiving without reservation and restoring that which was sundered. Returning to Issac, though, one wonders about the conversation held between he and Abraham after their journey to Mount Moriah. Perhaps the patriarch was forced to accept some error in his methods, if not intentions, when he mislead the boy rather than honour him with the truth."

"He could not know Issac would willingly follow his commands."

"As he did not bother to ask, nor Moses see fit to record such a conversation if it occurred, the matter is of course entirely speculative. Still, I can not help believing it would have been better if the two were united in their cause from the start—rather than one deceiving the other—as it rather spoils the metaphor of God the Father sending his Son to the world, unless one views it through the lens of a Marcionist heretic. There is no such deception at play in the parable of the prodigal; for all his faults, the younger son was always truthful."

"Yes: but, even if open in his words, he was deceived in his heart and therefore guilty of speaking against holy writ as personified by the fifth commandment. We may even say this sacred duty predates the Law itself, given the later embodiment of the Trinity and Christ's willing subjugation. The obedience we owe our betters is, perhaps, a universal precept."

"Although not without exception, given the revolutions in the Americas and on the Continent, or indeed the nation of Isreal when a king forfeited divine favour. Even our Lord did not enjoy complete congruity with his own kin. The metaphor of parental authority should never supersede the principal commandment, for that way lies idolatry."

"Perhaps we should dispense with metaphors as well." Dr. Prewitt spoke gently, with a smile, but in a more pointed manner than their intellectual sparring heretofore. "You are long past the role of student, demonstrating your competency even today. I hear nothing but good regarding your vocation. Therefore accept what I say not as a command but the advice of a friend who cares deeply about your future: do not let this rift continue."

After a moment's hesitation to ensure his composure, Henry replied, "I would welcome the opportunity to end it, as I have written many times."

"We both know General Tilney is a man of action. Mere words may not be enough."

"What then, sir, would you recommend?"

With a look of relief, Dr. Prewitt continued: "A sign of good faith that you are in no way opposed to him. I believe the coming Sunday where we say prayers for our king's safety and health would be a good one for you to attend, and leave Woodston to your curate. This public act would demonstrate your loyalties both as incumbent and dependent."

"I am not opposed, so long as it would not give offense."

"I will answer for it that your presence would be welcomed by all. Indeed, though your brother is bound by his duty, the viscount and his wife may be prevailed upon to come as well; it has surely been enough time since their nuptials that the request would not appear presumptuous. I believe your father would be very glad to host a family party under these circumstances. We may then hope to clear this misunderstanding for good."

"I hope I seek the same result as your kind offices are bent toward, but I must protest one point: there has been no misunderstanding between myself and the general."

"Now is not the time for your little quirks of language, Henry. I do not beg a confidence, nor have I inquired deeply into such a private grief, but as you remain celibate and faithful it must surely be a mischaracterization at the least."

"Why Dr. Prewitt, you would not excuse me of one sin only to condemn with monkery in the next breath?" He could not quite help the jab, and regretted his tone and words at once. "I beg your pardon for my levity. I do appreciate your efforts, but am obligated to say my troth is pledged if not consummated, and I consider myself as bound today as when last departing my father's abode. Any peace between us can not be achieved at the expense of honour, nor would halfhearted repentance result in anything of lasting value. It is consent, not pardon, that I seek; if you have laboured under a different understanding, please accept my apology for not undeceiving you at once."

After a long, awkward pause, Henry added: "If you still believe it would be acceptable, I remain willing to attend both you and my father a fortnight hence."

It became clear, after a few innocuous sentences breathed some vitality back into their conversation, that Dr. Prewitt was no longer sanguine of Henry's reception at this event, and by mutual assent the visit closed less than a half hour later. The vicar promised to pray for the restoration he continued to advocate even as its likelihood diminished in the minds of both men.

It had been a brief, pleasant interlude, conclusion anticipated yet unhappily achieved all the same, and which presaged many more months of waiting.

Chapter 24 from Northanger Abbey: "'And from these circumstances,' he replied (his quick eye fixed on hers), 'you infer perhaps the probability of some negligence—some'—(involuntarily she shook her head)—'or it may be—of something still less pardonable.'"