inspiration + perspiration = invention :: T. Edison ::

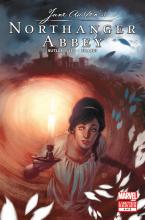

Jane Austen begins Northanger Abbey with these bold words: "No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine." Not quite as famous as Pride and Prejudice's "It is a truth universally acknowledged..." but just as evocative. That one sentence prepares us for a story that sets up common genre tropes only to subvert, bend, or outright dismiss them.

This satirical style is still popular (perhaps even more so) today. But Austen doesn't settle for mocking her characters. Instead, she mocks the preconceptions we associate with them, the trappings of fiction that may lead us, like Catherine, into seeing things one way when they are really another. And, while Northanger Abbey leans hard into parody (particularly in the hilarious first chapter, as Austen describes all the ways Catherine is not heroic), she soon dives deeper, and sketches out a narrative that doesn't just make us laugh, but think as well, that savors the comedy while also introducing actual danger, romance, and even character growth into the mix.

But what's with the clickbait title, tying Northanger Abbey to one of Marvel's most recent successes? In thinking about this idea (trope subversion), I realized WandaVision straddles similarly disparate conventions to explore a character who begins (and perhaps even ends) as unheroically as Catherine Morland. Spoilers for both stories ahead, so you have been warned.

WandaVision is a dramatic story told within the structure of American situational comedy television shows. The titular Wanda (aka the Scarlet Witch) retreats into the world of the Dick van Dyke Show, Bewitched, and more TV comfort foods from her childhood to escape the debilitating losses she has endured. Rather than stand up to be the superhero, she retreats inward. But the audience knows these shows as well as Wanda, and intrinsically leans into the beats we've been taught to expect, down to the ubiquitous laugh tracks.

We know from the start of Episode 1 that dinner with the boss will be a disaster, because that's the way it always plays out. We know misunderstandings will pile up, circumstances overwhelm, and disaster loom, only for the day to be miraculously, humorously saved within the allotted time frame. It's only when the camera work shifts to more ominous closeup as Vision's boss chokes to death that we realize there's more to this show than meets the eye, and begin looking for deeper meanings behind the pitch perfect jokes for each episode following. Wanda must learn that laughter helps us accept loss rather than merely escape it, and to face the consequences of her actions, to save the day in true Marvel fashion.

Catherine Morland is in a different place at the start of Northanger Abbey, carefree and unroubled. But she's also drawn to fiction, albeit the type popular for her generation: Gothic novels, meant to frighten rather than amuse. She looks for secret panels and villainous rogues as the most "genre savvy" character to hit a seemingly haunted house. Austen playfully teases her heroine and the readers with the over-the-top horrors to be expected, then cheerfully substitutes casual, even banal experiences, like when Catherine discovers a leftover washing bill instead of a secret hidden diary.

Then Austen pulls the rug out from under our rebuilt expectations by tossing Catherine out of the defanged abbey with no comic hyperbole whatsoever, demonstrating how powerless this girl is against a powerful man scorned. The separation she and Henry endure has the overwrought quality of teenage emotions and yet with the gut punch that they might truly never see each other again. Indeed, one fan fiction author explored that very possibility, showing how natural it would be for this frothy story of young love to go in a different direction. Their reunion is that much sweeter because danger, even loss, threatens them, not by overwhelming the satire, but nicely playing with the very tropes Austen has challenged throughout. Catherine becomes a heroine by learning from her mistakes and dealing with the messy reality of the world.

Importantly, neither WandaVision or Northanger Abbey condemn their mediums. Sitcoms are not bad, nor are Gothic novels: in fact, they may teach us a lot in the right context. It's the degree to and way we allow them to influence us that marks the experience as positive or negative.

When I began Gentlemen of Gloucestershire last year, I had very few ideas picked out ahead of time. I knew the central conflict I wanted to drop my characters into and where I wanted it to end up, but the exact plot was largely undefined. However, I did know I wanted to imitate the style of the original as much as possible. That meant not only using Regency language and Austen's characteristic wit, but also the way she played with genre conventions to tell her "unheroic" story.

A canonical Jane Austen love triangle, as full of angst as any fangirl could want.

A canonical Jane Austen love triangle, as full of angst as any fangirl could want.

For example, in the opening pages we have the setup of a standard love triangle. I've seen this idea explored with nearly ever pairing, from the conceivable to the outlandish. There are beats readers come to expect: the woman will be pursued by two men, and in Austen fandom it's often the villain and the hero vying for her affections. Sometimes the heroine even uses the villain to inspire the hero's jealousy! Hijinks ensue, tragedy threatens, but at the last minute the One True Pairing emerges.

To subvert the trope, I wanted it clear from the start that Captain Tilney is not actually interested in his sister-in-law. Instead, he's performing a role, one we as the reader may expect from past stories, but which a still very innocent Catherine just doesn't quite get. Yet even as she's unsure about the details, she does everything she can to maintain her distance while still keeping within social roles of the time. Henry walks in on them just as we might expect, but doesn't develop instant suspicions of his wife Othello-style (remember, he's fonder of the comedies!) When the big confrontation between the men occurs, it turns out they're not even arguing about the same thing: Catherine isn't "won," since she was never at stake to begin with.

There's still comedy in these scenarios, but the laughs come from playing the situation straight. Indeed, readers may think Chapter 5 could easily conclude the story at this point, because where's the central conflict for our characters to grapple with? How can any couple survive a pastiche without continually doubting each other and needing constant reassurance of their loyalties? I won't say too much since the main plot is about to kick in with this week's installments, but be on the lookout for ways the characters play against type or find "novel" approaches to common predicaments.

Fan fiction gets a bad name for being derivative, thinly veiled wish fulfillment, all fluff/angst and nothing more. The truth is there is a lot of that kind of fiction out there, both of the "original" and fanish persuasion. There are plenty of great fan fiction stories out there, and authors are certainly capable of finding their own voice in the worlds created by others.

Sometimes, the most unlikely idea flowers into a unique creation. I doubt anyone before this year could imagine that the most popular Marvel offering after Endgame, a smorgasbord of brawny superhero action, would explore a young woman's psyche through old TV shows. Similarly, I never expected my first novel to draw from one of Austen's more obscure early works.

I think what elevates both works is how they never fall into outright caricature. WandaVision keeps a genuine appreciation for its sitcom beginnings even in its action packed finale, and Northanger Abbey provides the protagonist with a satisfying climax which echoes the terrors Catherine had earlier imagined while still keeping a tongue-in-cheek style. Subversion for the sake of subversion may be cheap and unsatisfying; subversion for the purpose of telling a good story may introduce readers to untold variations they didn't even know they were looking for.

Perhaps instead of subverting tropes, I should say the goal is to surpass them: finding new ways to explore old ideas.

How will my little sequel do in pursuit of this calling? Time and you as the reader will tell. I'm already blown away with the responses, and appreciate each and every comment that's come in so far.

I'd love to hear your thoughts as well on the topic of trope subversion or upending genre conventions. What are you favorite examples from popular media, or in Austen's own works? Do you have a favorite fandom topic to read, some comfort food you always return to, or is there anything that you avoid? And let me know if there's a future topic you'd like me to explore as we dive deeper into the world of Northanger Abbey.